19 November 2021 – There’s no denying that the UN Climate Talks in Glasgow had some successes. The commitments on closing the rulebook on carbon markets, deforestation, coal divestment, internal combustion engine phase out, and methane reduction are important if they prove to be material. They do set the tone and mark some level of progress.

In addition, no one can deny the importance, if truly implemented, of some of the incredible announcements made through the Marrakesh Partnership for Global Climate Action, bringing together nearly 8,000 non-state actors (including 5,235 businesses, 67 regions, 441 financial institutions, 1,039 educational institutions and 52 healthcare institutions), committing to halving emissions by 2030 as part of the Race to Zero, and the 5-year plan to deepen engagement with regional stakeholders launched by UN Climate Champions. These announcements coupled with promises to enhance the implementation of non-state actors’ commitments, and the development of tools for accountability across mitigation, finance and adaptation, are positive as is the Glasgow Financial Alliance US$130 trillion pledge of mainstream private finance to transform the economy for net zero.

But how is it possible that once again countries left Glasgow without delivering more ambition in their own national climate commitments or finalizing an agreement on the $100 billion annual support for developing countries? In addition, except for financial pledges from Scotland and Wallonia, Belgium there was no agreement on loss and damage. In the words of Saleem Huq (my esteemed co-Chair of the UNFSS Resilience Action Track, also leading the loss and damage negotiations for the Bangladeshi government and the Climate Vulnerable Forum), this is bullshit!

Despite most of us expecting that we would not get the deal needed, there was a great deal of hope in Glasgow. On many levels there was a growing understanding that systems transformation was no longer just an option but a necessity, and that technology was not the silver bullet but only one of many tools in the toolbox alongside finance, governance and just transition levers all working together towards broader systems change. Despite this, the negotiations and final agreement totally missed the point on transformational proposals and the sense of urgency. There were clear calls for immediate emergency action expressed by many of us both prior to and during the talks. As stated by Antonio Gutiérrez, Secretary General of the United Nations in his closing remarks “the political will was not enough to overcome deep contradictions… It’s time to go into emergency mode”.

The only way to rectify the failings in Glasgow will be to first put in place key accountability procedures to ensure that the commitments made actually do transpire and are properly monitored, reported and verified. Secondly, it will be essential in the run up to next year’s COP for countries to come forward with more ambitious greenhouse gas emissions reductions (in terms of Nationally Determined Contributions), in particular for 2030 (closer to 55-60%) and 75% by 2040, and to put in place all necessary levers so that the $100 billion is transferred to countries that need it by early 2023 at the latest!

No one says any of this is easy but it is the only way to emerge from emergency.

STRESS TESTING COP26 PLEDGES AGAINST THE PLANETARY EMERGENCY PLAN 2.0:

Three years ago, I co-wrote the Planetary Emergency Plan published by the Club of Rome and Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. The Plan clearly states the actions and urgency needed to emerge from emergency and to stay within the planetary boundaries. It specifies the 10 commitments needed to preserve the global commons and 10 actions to create just and equitable societies; transform energy systems; and shift to a circular and regenerative economy.

Checking the outcomes of COP26 against the Planetary Emergency Plan actions shows that we are nowhere near the action needed to limit temperature rise to 1.5C degrees, let alone address our climate, health and biodiversity tipping points at the same time. Three years after its original publication, are we any closer to emergence from emergency?

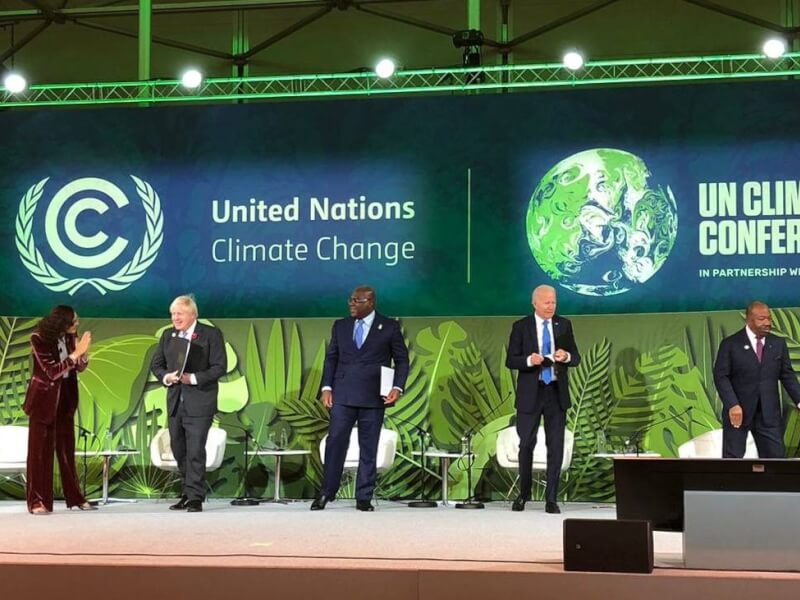

Looking at our 10 commitments for the global commons, the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use; the Forest, Agriculture and Commodity Trade Roadmap; and the Global Forest Finance Pledge – which I had the pleasure of launching with world leaders’ during the World Leaders Summit Action Event – provide clear steps towards halting and reversing deforestation and land degradation by 2030. This is a landmark package of action. Nonetheless it is five years later than recommended by our Plan. The Declaration represents the first time a COP Presidency has convened such a large group of leaders specifically around Forests and Land Use. If the 141 countries that signed up to this commitment are able to deliver, this will represent a huge win in terms of getting the world’s lungs back as it covers 91% of the world’s forests and also directly protects the lives and livelihoods of the indigenous communities protecting our forests thought the necessary financial assistance. In the upcoming months, it is crucial to agree on metrics and reporting processes to ensure accountability and monitor implementation on the ground.

When it comes to our stress testing, the notable global ambition on forests (thanks in part to the incredible work behind the scenes from our Planetary Emergency Partners and the UK Government) was sadly not matched by action to protect our wetlands, grasslands or savannahs, nor the Arctic and the cryosphere (beyond a general reference in the preamble of the Glasgow Climate Pact) including stopping the exploration and exploitation of oil and gas reserves as called for in our Planetary Emergency Plan. It is also clear that the protection of oceans and vulnerable ecosystems is only just starting – with a call for an annual dialogue on ocean-based action. More commitments to protect our critical global ecosystems must be set in stone and funding pledged by countries if we truly wish to protect our global commons and set nature on the path to recovery, as recently underlined by myself, Achim Steiner (Executive Director UNDP) and Frans Timmermans (Vice President European Commission).

Although we can agree that COP26 does come some way in achieving our first point on protection of our forests both by halting deforestation and stopping the trade in commodities putting our forests at risk, other land use issues linked to food and fibre such as regenerative land use and a shift away from large scale industrial agriculture did not feature in the official negotiations. On the side lines and through the Race to Zero campaign, the role of regenerative agriculture and the need for low carbon food systems was featured through many events and the launch of the Food Forward Consortium and Regen10, which we are proud partners of.

When it comes to transforming our energy systems, the Glasgow Climate Pact includes language on the “phase-down of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies” but falls short of the actions and deadlines laid out in the Planetary Emergency Plan to stop all fossil fuel expansion, production and use by halting subsidies and shifting revenues and investment to low-carbon deployment by 2025. The lack of mention of an oil and gas phase out is an obvious omission, but the inclusion of non-carbon dioxide emissions including methane (e.g., the Global Methane Pledge driven by the EU and US which commits to limit methane emissions by 30% by 2030 – signed by 105 countries and launched during COP26) is important, even if the methane pledge does not have some of the most needed oil and gas producers on board such as China, Russia, India, Iran and Australia.

A crucial part of our 10 point planetary emergency action plan is the human dimension and a just transition. The explicit reference to the importance of ensuring a just transition and the establishment of an $8.5 billion public finance fund for a Just Energy transition for South Africa should get an honourable mention but apart from these efforts COP26 has been widely criticised for a lack of inclusion and diversity. Luckily some important indigenous delegations did make it to Glasgow. My conversations with some of these groups in particular indigenous women from the Amazon highlighted the lack of transparency in all decision making of the impact on indigenous peoples; the little funding and support allocated; and the corruption in so many of the tropical forest countries. The deep sense of disappointment and anger expressed by these women showed once again that the world’s most important caretakers of our global commons are marginalised, or worse, currently murdered for profit and power. An immediate transfer of funds directly to these communities through transparent funding mechanisms is therefore the only way forward.

In fact, let’s be clear – the links between climate and COVID and healthy people on a healthy planet were largely absent from official decisions and communications. Therewith we missed an important opportunity to build on our learnings from COVID and an incredible possibility for transformational change. So, our joint calls for a systemic approach taking into consideration people, planet and prosperity and building resilience to multiple shocks and stresses, were left unanswered.

THE CASE FOR SHIFTING FROM EMERGENCY TO EMERGENCE

Economic systems transformation is at the core of the Club of Rome’s work and ethos. For the last 50 years we have warned of the need to shift away from the current economic paradigm, which is based on short-term profiteering and GDP growth rather than placing a value on what matters, whether it be natural- or human capital. There was some progress in bringing in systems thinking across sectors but it is time for our leaders to recognise that our economic and financial systems are deeply broken and climate change is a symptom of our model of growth at all costs. To do that, we need to prioritise sustainable production, consumption and investments as outlined in the Club of Rome’s Planetary Emergency Plan, while taking into account issues of poverty, equality and equity.

We know that 75% of G20 citizens are ready to embrace change, so we must use this unique opportunity in time to catalyse the deeper transformation necessary to build resilience in our economies and ensure greater wellbeing for all. This was the essence of our Futures Lab event on transformational economics hosted by the UNFCC and High Level Champions for Climate Action as part of the global climate action agenda.

Next year is the 50th anniversary of ‘The Limits to Growth’ – the landmark report to the Club of Rome. The economic scenarios from the report pointed to the 2020’s as the period in time where multiple environmental and social tipping points would converge. We are in that moment in time where these tipping points are leading us to a state of emergency and that is where my disappointment lies with COP26. We cannot say that the approved measures allow us to truly emerge. However, as lead-author Donella Meadows put it: “There’s too much to do to allow complacency, and too much opportunity to justify despair!”. Let’s make sure that the next few months and year are used for targeted action and holding countries accountable for their promises so that we both achieve more ambition at COP27, emerge from the current emergencies at hand and catalyse real transformative change.

The Club of Rome at the UN Climate talks